Published in 2012 in the catalogue of Peeter Laurits

"BRIDGE TO BEYOND AND BACK"

I’m not quite sure why I want to phrase my question like

this, but it seems to me that it isn’t possible to approach your creative work

without the category “joke”. And I don’t mean “joke” as a social or political

release valve or as an act borne by an ideology of domestic amusement. Rather,

I mean “joke” in a mytho-poetic sense that turns different strata of cultural

history upside down, makes them absurd, drags them out of their embedded

meanings. And perhaps I also mean Beckett-like existential jokes that reconcile

us with the solitude of our existence. That’s why I’d like to ask, what’s your

take on “jokes”? And do you know any good anecdotes?

I’m not a Christian, a Jew or a Moslem. That’s why I don’t think that the world

has ever been completely finished. Creation continues and language is the most

important building material in mankind’s world. Jokes, in turn, are the

generator of language, creating new meanings and changing old ones. The cosmic

potential of human language is concealed in jokes. We create new models and

different kinds of worlds by shifting the polarities and semantic fields of

existing concepts. This applies both symbolically and in reality.

Language is not simply a tool for describing and analysing reality. We also generate reality through language. The reliance on feedback goes both ways. Language and mentality belong together.

The company of people without a sense of humour quickly becomes very boring. It’s as if they live in a finished model where one can do nothing but submit to its parameters. That’s a secure existence, but its one that closes quickly. It’s difficult to point out something beyond the sphere of our experience using the means of ordinary language. On the other hand, openings through which eternity and infinity can be seen can be created by turning and twisting language. Jokes are one way of presenting the fact that the unpresentable exists.

I have sometimes been accused of not taking anything

seriously. That is definitely true and it is definitely not true. But I can

never remember anecdotes. I can’t particularly be bothered to listen to them

either, at most five at a time. After that it gets boring. If a joke is

canonised, then it isn’t worth anything anymore. Then it becomes part of a new

finished model.

You’re currently back in Kütiorg as you write your answers to these questions,

but just for a while since you don’t live there permanently anymore. It’ll

probably only be possible for you to say what that period in your life meant

after a few decades. Yet when you’re in the city and you sometimes close your

eyes or you have dreams, what do you feel first in relation to Kütiorg? Views?

Odours? Colours? Do you see your neighbour? How do you remember that part of

your past?

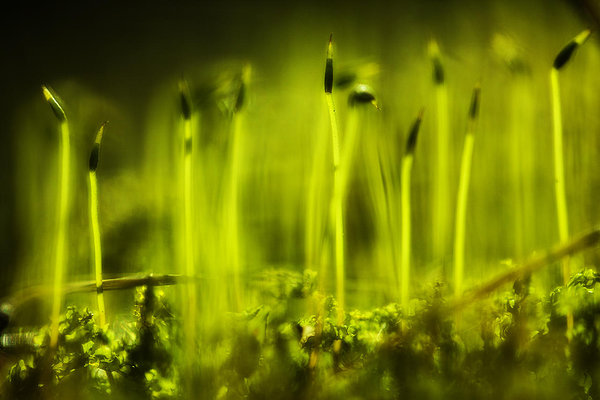

I remember waking up in Kütiorg as escape velocity, a

velocity that took me out of the gravity that was in effect at that time. I

remember it as an explosion where I understood Nietzche’s longing as I cleaned

up my art teacher’s abandoned studio at the same moment when I no longer

consisted of pieces. But I discovered myself splattered about on a carpet of

moss that is so much bigger than I myself was that I don’t have a single word

to describe it. The carpet of moss is bigger than mankind, bigger than the

semiosphere.

My memory of Kütiorg is the scent of opening my eyes in the bosom of a gigantic linden tree. The linden is in bloom. Its branches hang heavy under growling honeybees. The sky glares through the branches and through the sky hurtles the speed of light, rolling everything up after it so as not to get in the way of time. Actually, part of this writing was written in Kütiorg when I was visiting Leelo and the other half of it in Holland while visiting friends in Groningen with Karina. Our friends took us to stay in Onland, a wonderland on the outskirts of the city. The car stopped in a secure, orderly Dutch alley. Two identical houses. Neither house has curtains according to Calvinist custom. The living room is in full view so that nobody could have any suspicions, and two real silver plated vases paarisvaasi made of plastic containing identical flowers or painted branches showing off in the large living room windows of both houses (as in the large living room windows of all the other houses here).

But a narrow hedge of arbour vitae submerges into the

darkness between the two houses. There is a deep ditch on the left because we

are going towards a bog. There are trees on both sides like a wall. It isn’t

possible to spread your arms out because the passage is narrow and dark like

Carroll’s rabbit-hole. Then we reach a tree that has been stricken down by

lightening and behind it everything is as if in a fairy tale. A bog island

pulsating with life, with groves of oak, hazel, arbour vitae and bamboo, with a

carpet of moss instead of a lawn, and with little bog pools, where herons don’t

pose but rather fly over you in flocks and where grass snakes splash among the

bog violets. An incredibly lovely hippie nest is woven into this paradise. The

houses are built with joy like children’s playhouses but there are many of them

and they form a village. Our hostess Anneke, has filled this place with that

kind of people, with the kind of tensile and bright life that the bog continues

to softly sway to this day.

You can try to guess which of my answers were written in Kütiorg and which were

written in Onland.

If we place your so-called Kütiorg works on a chronological

axis, an interesting sense of tension can be seen in my opinion: on the one

hand, they tend towards the primeval past. It is as if they search for the

moment of the beginning or for ancient dreams. On the other hand, however, and

on the contrary, they also pull us into the future, which can simultaneously be

both apocalyptic and catastrophic, yet at the same time also poetic. What is

your relationship to time?

I don’t know. None of us really knows what time is. I look

at time through a magnifying glass and it looks back at me through that same

magnifying glass. We ourselves, people, have made up time and so consequently

we have to keep thinking about what it is.

I try to stretch my horizon of time as far as possible but

it’s like mountain climbing – sometimes I’m in a ravine and I can’t see

anything, then sometimes I’m on a mountain ridge and can see quite far. I

admire Uku Masing’s range, who delved deep into the Neolithic age and

contemplated 40 000 years into the future. Now try to imagine Hindu cosmology

that counted in millions and billions of years by way of kalpas – from Brahma’s

day, which lasts 4.32 billion years, to Brahma’s year, which is the length of

the universe’s full cycle. This kind of horizon of time makes me speechless and

inspires me. Man’s duration in Brahma’s vortex of time is rather fleeting. It’s

great to be plankton in the ocean of eternity. The concept of time is very thin

in Christian civilisation but in return, it is very bureaucratically mapped

out. It’s a rather small step from the Nuremberg egg to the Excel table. That

is probably quite inescapable in the logistics of the masses.

The tempo of mankind’s population growth had increased by the mid-20th

century at such a frenzied pace that from that point onward, the number of

people alive at any given time always outnumbers the total number of deceased

persons from all the preceding ages. “The living outnumber the dead.” This is

an immensely appalling turning point in the evolution of civilisation.

Viewpoints of the interests of the moment voted down supragenerational

viewpoints through demography. It seems to me that mankind’s horizon of time

started narrowing around that time. Isn’t it dangerous to hurtle with explosive

acceleration in some particular direction while at the same time our horizon of

time is still poking about right under our noses? I think it’s dangerous and

rather ignorant. Apocalyptic if you wish.

I remember that you once related how sometimes when you were

living in Kütiorg, you picked the cat up in your arms and it led you to

unfamiliar places. In my opinion, it is fascinating to consider the spatial

pressures reflected in your work. In many cases, you have tried to map out

something that is impossible to map out, in other words to create vectors,

trajectories and orbits in spaces where they inevitably remain absurd, poetic

or inadequate, almost lying: Heaven’s atlas, Ragnarök, but also different

mappings of Kütiorg, and of course labyrinths as well. Can some kind of passion

to deny the possibility of a state of completion (fixation) be seen behind

impossible spaces and endless errancy and misleading? In other words: do your

spaces reflect your wish to be a river? Or is there something else?

The name of that cat was Hippolit. He consisted of stripes

and will. Sometimes I performed my rituals, renounced my ego and desires,

picked Hippolit up in my arms and went into the woods following his directions.

The cat is such a lissome animal that you easily understand in which direction

his thought stretches itself when it is in your arms. So as the cat’s horse, I

really saw the woods in an entirely new way. I flowed along both as the cat and

as the woods. Hippolit showed me the woods through his own eyes.

Once I lay poisoned and naked beside a dying campfire. My body was covered with mosquitos. They sucked poison from my veins. They came and went. Came and went. Each mosquito that left with a little drop of my poison left behind a link to its eyes. I saw the Valley through the eyes of hundreds and thousands of contented mosquitos. All at once. And not simply through eyes. Through compound eyes. Through cassette eyes. Through shrapnel eyes.

There are far more possibilities of infinity than there are of completeness. I’d like to map that out but I can’t. Then to simply motion in that direction, to allude to those gates.

If we look at the diagram of the labyrinth on Greek coins or Neolithic ornaments, it is obvious that it’s impossible to lose one’s way in that kind of structure. The labyrinth is identical to Ariadne’s Thread. The labyrinth is a mandala, a spiritual orifice through which one passes into infinity and one’s own central point. At the same time, most of my Labyrinth pictures are very claustrophobic. Compressed perspective and closed planes where a little light seeps in only through cracks. I didn’t notice that at all when I made those pictures. It’s only now that I’ve started seeing them as metaphors of Plato’s cave. It’s probably necessary to come out of that cave.

That Renaissance-like linear perspective captivates and

disturbs me in relation to the camera. It is enchanting but it is also

constrictive. I’m attracted to it but I try to escape it. Labyrinths with space

pressed against the wall was one possible line of escape. The aquariums in

minimised focus in Korea päevikud (Korean Diaries) were different. There

are probably tons more of those lines of escape. And central perspective will

also probably earn ovations. The central perspective is one of many splendid

perspectives. And there really are an awful lot of perspectives, flocks of

them, like migratory birds. I want people to be able to experience this through

my pictures as well.

A garden where only one type of plant grows is called a field and sooner or

later, the scythe will be applied to it.

Who do you move about as in nature? And

who would you like to move about as?

I’d like to move about in nature as an elf.

As someone who was born there and makes his own paths. I was born in the city,

I’m a nomad. That’s why I roam about here and there.

The cat taught me to listen to all creatures simultaneously while moving about

in the woods, from the tiniest to the most monstrous, from earthworms and aspen

leaves to the aurora borealis. An earsplitting crescendo, an oratorio in which

the sounds of human space sound like a hive somewhere moving off into the

distance.

Have you sometimes thought that your

photographs look as if death has already occurred?

I sure hope so. Death has long since occurred and it will

have long since occurred in the future as well. Death is the greatest ärasus, it will never end.

Death’s garners are bottomless. It exists all the time.

To Have Done with the Judgement of God

The hostess of the hippie nest in Holland under whose roof we are currently living has been full of cancer for seven years already and takes every morning as a happy surprise. She has an incredibly lovely house for sleeping made of glass in her yard. She told us how her funeral is planned. “First of all I will be dressed in a very pretty burial dress, the one that is hanging there on the outhouse wall. I should probably wash it soon. Then I’ll be placed in that glass house there. I’ll be decorated with feathers and flowers and I’ll be shown to the sun and the moon. Some of my carpenter friends will make me a coffin out of rough-hewn pine boards and then I’ll go on my way.” So there. That’s how death is looked in the eye while smiling charmingly.

Estonia’s photography scene in the 1980’s was something

altogether different from what is was in the 1990’s. The beginning of your

creative work falls right in that pivotal time: photographs in the 1980’s were

not yet art, but in the 1990’s they were very in. Did that at some point make

you re-assess what the art of photography means to you?

I have always had to re-assess the art of photography. As a

child, I was an idea person. I read, thought and wrote. I don’t remember the

visual as being of any particular importance for me. In the first grade, I won

a Smena 7 camera as the main prize of a writing competition held by the

newspaper Säde. I photographed a hedgehog, my godmother and the

Vastse-Kuuste pharmacy. It wasn’t credible. The camera remained in my cupboard.

In the eighth grade, I used it to duplicate pornographic pictures and pictures

of bands to earn some pocket money. That wasn’t credible, either. In my

adolescence after becoming bored of the art of painting, I came up with the

idea of using the camera to test the limits of what is credible for people and

what is not. It seemed interesting. It seems interesting to this day. A lady

expressed sympathy for the Baltic countries at the Berlin exhibition of Mullatoidu

restoran (Dining with Worms) because life is so bad there that corpses lie

about here and there at random. A former female classmate of mine asked about Euroopa

pärast vihma (Europe after the Rain) if I photographed it in Iran. Splendid

compliments.

I photograph my thoughts and dreams. They could just as well

be painted or drawn. I’ve tried that but I respect precisely that kind of

spectral veracity that photography affords. I’ve also thought about filming, I

constantly think about it but until now the enchantment of the frozen moment

has suited my works better.

I know that you appreciate beautiful things: calligraphic

handwriting, picturesque flowers, precise usage of language, tasteful wine.

“Beauty” is perhaps very important to you? And not only visual, but rather

beauty that caresses all the senses? Why?

There has never been a consensus in any era concerning beauty and nobody knows

the formula for beauty. Very many have searched for it. It seems to me that

whatever something starts up when someone tears himself free, goes beyond his

limits, is very beautiful. The essence of beauty lies somewhere in the sphere

beyond words on the other side of rupture. There is almost always some element

of imperfection in beauty, some sort of crackle, a fart or something

overwrought, but it is a very economical way to present the fact that the

unpresentable exists.

You very often use the vertical dimension in your works,

although, for example, you wrote in your diary during the time you spent in New

York in the early 1990’s that your eye is tired of urban verticals and that it

seeks the horizontal. Can the vertical in your works be interpreted

religiously, if under religion we refer not to any single specific confession

but rather to religiousness somewhat more broadly as the belief in the

existence of a certain higher non-reality (sanctity?)? Or is the vertical

simply a visual coincidence?

The religiosity of the vertical is not a coincidence and I also ask that the

horizontal be interpreted in religious terms. I feel that the Sacred does not

manifest itself in the vertical alone, as singularity, but also through the

endless diversity of the horizontal. Somewhere in infinity, singularity and

infinity meet. I’m not associated with any particular confession but I perceive

the entire world as a divine, soulful revelation. When I lived in New York, I

often got tired of the vertical world. My eyes wanted to rest and then I went

to Brighton Beach to soothe my senses. The ocean is marvellous. There you can

clearly see that beyond the horizon there is another horizon, and behind that

is the glimmer of horizons. And you can dive into some horizons like into a

tsunami.

The motifs of your Kütiorg works originate mostly from your

nearby surroundings: Southern Estonia and its mushrooms, stumps, decayed pieces

of wood, valleys, forests, fog, mosquitoes, brooks, snails, old houses, and so

on. Is the fact that you photograph your intimate surroundings nearby and place

your surroundings in new contexts in some way also a way to bring order (or

conversely: to amplify) to the chaos and spontaneity around you? Or is it the

safest way to create art? Or is it coincidence? Or something else?

Like I said, I don’t photograph things or views but rather

my own thoughts. That is the most intimate part of me. All of my creative work

is entirely autobiographical. By photographing my internal world I am also

cultivating and tidying it up. Something a little bit like the work of a

gardener.

Motivation can also be described through ownership of land. This is my land. I look after it, live it and photograph it. Among the Australian aboriginies and many other peoples, the ownership of land is passed down matrilineally. The mother gives birth to her child on its own land and gives to the child everything that belongs to that land – vitality, songs, traditions, the story of creation and ancient dreams. From the moment of birth, the child belongs to that land. The child is obligated to maintain everything and to pass it on to others. Land ownership in native cultures is usually not prescribed through rights but instead through obligations. This is more understandable for me than the perception of owning land in the Christian legal system.

I’m a nomad who was born in Tallinn’s Central Hospital. I belong to the land where I happen to find myself. When I live in the country, then I sing the country. When I live in the city, I sing the city. I am obligated to preserve everything and to pass it on to others.

Art that refers to itself as being social no longer

interests me. It never interested me. First of all, there is no such thing as

non-social art. Art is activity directed at intercommunication. The codes of

communication at the disposal of art make it possible to address fundamental

values and to affect them directly. It seems superfluous to me to pry at some

isolated incident or other in the social community or to unravel someone’s

factious private interests with the aid of such fundamental codes. I don’t

believe that art should comment on internet commentaries. Social art subsidised

by the European Union is like running past oneself backwards with the help of

leasing.

Can you specify what that state of mind

is that gets you going creatively? Is it sadness, joy, melancholy, a perception

of tragedy, or something else?

That state of mind is known as exultation. The exultant joy of participating in

something endlessly powerful. I feel awfully good in that state of mind.

You have recalled your conversation with a stork early in your life when you

were still a little boy. Do you feel that after these photographs there is more

today that you can talk about? What do you talk about with the stork?

You see, when I talked with the stork, I didn’t know how to

talk yet. We were able to converse splendidly. I don’t know the language of

birds anymore now. But I practice all the time.

When I lived in Kütiorg, I learned that it isn’t necessary to talk very much.

It’s more important to listen. And when you are understanding something, then

the answer flies to you all on its own.

How near to your heart is the “trickster”? Is there something similar in your

and his aspirations? And how can you still be a trickster when you are no

longer surrounded by primeval forests and ancient dreams and instead you are in

the middle of deadlines, supermarkets and blockages in sewage pipes? How

oppressive (or delightful?) is the life of a contemporary Western man for you?

The life of a contemporary Western man is extraordinarily

oppressive for me. We’ve been born into ruins. I think that the life of a man,

or woman, in any given golden age would be just as oppressive for me. Being

born in a body is no bed of roses. The body’s hieroglyphs are desire and pain.

I think, and many others have also thought, that the Shivas started physical consciousness up in a joking mood so that there would be some kind of substance that could be aware of them and with whom they could crack jokes. Work with that then. Why tell anecdotes among yourselves, crack jokes with the wittiest of all. So what if it’s no laughing matter in the form of substance. First your back starts to creak and then your thoughts start creaking and before you even really get into the swing of things, the operational system turns out to be outdated already and the cells have forgotten their original function. If you’re going to keep company with anybody, then the trickster the one to be with. Don’t believe that the world is already created in finished form and that it is the best of all possibilities. That’s ignorant superstition. The world has to be constantly recreated, kept alive and passed on. And it has to be looked at directly from every possible and impossible angle. And you have to smile charmingly.